Executive Summary

Global Atomic Corporation is a uranium development company with a difference, a company that stands alone, in a Category of One. The two key differentiators in Global Atomic are the Dasa deposit itself, and the fact that its stake in BST is a financing chip that can be cashed when it comes to building Dasa.

The Dasa uranium deposit is a phenomenal discovery and is perhaps the most important mineral resource globally that will start production in the current uranium cycle. Dasa is large, with over 250 million pounds of mineralised material that has high grade intercepts open at depth and along strike meaning that the deposit has the potential to be even bigger than currently defined. It is the kind of resource that can sustain decades of production and it therefore has strategic value as a long-term source of supply for the long-term, strategic nuclear power generation industry. Dasa also has a high-grade front end that Global Atomic has designated as the target of a Phase 1 mine plan. This plan, laid out in a recent PEA, is to mine 0.5% grading material over twelve years to produce over four million pounds of yellowcake a year at $18/lb AISC and a capex of $203M.

Economically and technically Dasa is better than any other project globally, apart from potentially one or two of the Canadian deposits in the Athabasca, but crucially it can be permitted within months whereas the Canadian deposits will take decades to permit. Global Atomic aims to have the mine permit in hand within a year before entering feasibility and the path to construction.

The 49% stake in the recycling business in Turkey, BST, will take two years to pay off its debts before emerging as a regular source of meaningful cash flow, potentially worth $100M to the Company. Global Atomic will be able to use the value of BST to reduce equity dilution when it comes to financing Dasa.

Challenges for Global Atomic are managing security risk in Niger, filling out the leadership into a properly staffed, build-ready team, tightening up the language it uses in the market, and topping up the treasury to ensure that the Company is well funded for the next two years.

Share valuations start from C$1.38 per share if the contract uranium price is $35/lb in two years’ time and the company share count stands at 300 million, rising to C$2.60 if the uranium price reaches $50/lb. Currently, the Net Asset Value of the company indicates a value of C$2.40 per share, which is four times higher than the share price today.

Your decision to invest (or not) should primarily hinge on your view on the uranium price and your assessment whether Global Atomic can replicate the security measures that Orano has in place to ensure uninterrupted supply of uranium from Niger. Crux believes that Global Atomic offers compelling value in a rising uranium market.

Introduction

Global Atomic is a development company with uranium assets in Niger, and operating cash flow from a zinc business that makes money from recycling steel dust in Turkey. The company is headed by Stephen G. Roman, an industry veteran with a uranium background who has built up an exploration and development team around him. Global Atomic was formed in 2005 as a private company, and in 2017 it merged with Silvermet, another Roman vehicle, that owned the recycling plant in Turkey and was listed on the TSX Venture exchange.

The Company aims to start uranium production at the 100% owned Dasa project, and it has just published a new PEA based on an optimized twelve year mine plan. Global Atomic is now in the process of applying for a Mining Permit prior to moving into the Feasibility stage. The Company anticipates receiving the Mining Permit in Q1 of 2021, and aims to have completed the Feasibility Study in early 2022.

In addition to the uranium project, Global Atomic has a 49% stake in the BST steel dust recycling operation in Turkey that produces zinc concentrate and provides financial leverage to minimise equity dilution. The plant was expanded in 2019 increasing throughput capacity to 110,000 tonnes annually up from 60,000 tonnes a year. At full capacity the expanded BST could produce 60 million pounds of zinc concentrate a year, although the Company has issued guidance that 2020 output is expected to be approximately 45 million pounds, suggesting capacity utilisation of approximately 75%. BST is carrying US$22.85 million of debt at the project level, which it expects to pay off in two years.

Strategy. What is the Company planning to do?

Global Atomic plans to bring the Dasa uranium project, in the Republic of Niger into production and in interviews Stephen Roman has stated that the team are miners, and that Global Atomic is a mining company. The website and presentation also promote the fact that the Company has a non-dilutive strategy as the company is supported by cash flow from the recycling facility in Turkey; and a potentially low-cost route into production through the trucking of ore to Orano under the terms of an MOU signed in 2017.

The strategy of the Company does seem to have changed over recent years. In late 2018 the Company published a Preliminary Economic Assessment (“PEA”) on Dasa, using a US$50/lb uranium price with a capex of US$320 million, with a view to producing 7.5 million pounds per annum on production. These results put the project in the same category of almost every other uranium project, which is to say a high capex project profitable when uranium prices reach US$50/lb. Given the fact that uranium prices were firmly entrenched in the US$23-25/ lb range, plus final the results of the drilling from 2018 were only published in early 2019, Global Atomic soon announced that it would reanalyse the project, with a view to it being profitable at low prices. The fruits of that work has been revealed in the new PEA, published in April 2020.

Also included in the 2018 PEA was a section devoted to the Alternative Mining Strategy which involved trucking ore to the Orano operations at Arlit some 120 kilometers to the north in Niger. This was seen as being a key way of getting started in a low uranium price environment, with reduced capex. The Company regularly refers to its ability to get into production quickly by trucking ore to Orano, and Stephen Roman often mentions this option in interviews.

It is interesting to note that the new PEA, published in April 2020 envisages a standalone operation, using a US$35/lb uranium price with a capex of US$203 million. The news release from 15 April 2020 does reference the Orano MOU in a section at the end of the document titled ‘Value Opportunities’, but the preferred strategy appears to have evolved into a standalone operation, without trucking ore to Orano.

The shift in strategy is understandable when looking at the strength of the new PEA. The Phase 1 mine plan is for a high grade, low-tonnage underground mine that generates strong economics. Thanks to the grade being so high (average life-of-mine grade, 5,396 ppm U3O8), the tonnages are small (1,000 tonnes per day is a small mine) so every aspect of development is modest, leading to a manageable initial capital requirement of US$203 million. The previous PEA needed a higher uranium price to make it work, plus a much higher initial capital requirement, which made it a good candidate for trucking ore up to Orano at Arlit. The disadvantages, however, were threefold. Firstly, by selling ore Global Atomic would have probably entailed losing control of the yellowcake end-product. Secondly, the logistics of trucking ore safely across over 120km of desert in Niger are non-trivial, both in terms of cost and safety. Thirdly, by outsourcing the processing the Company effectively cedes control of the project to Orano. In an oligopolistic industry such as the uranium industry, handing control to one of the major players tends limit strategic options for the Company.

In short, with the new PEA published, the benefits of reducing the upfront capital and trucking ore are now less clear-cut. The capital expenditure per pound of production required for Dasa is very low by industry standards, plus the project is economically robust at low prices, which would make raising the initial capital much more feasible. The project remains whole within the compass of Global Atomic and the government of Niger, the awkward trucking across the desert is removed, and all-in-sustaining-costs are below US$19/lb.

The final strategic nuance evident with Global Atomic is that the BST plant in Turkey was incredibly valuable to the Company in 2018 and

2019, and it will be again in 2022 and beyond, but that there is a lull its punching power in 2020 and 2021 due to Covid-19, low zinc prices and debt repayment. In 2018 BST funded the drilling discovery of the Flank Zone, and in 2019 as Global Atomic used BST to explain to the market that the valuation was covered by BST meaning that the Dasa uranium project was ‘in the company for free’. In 2022 when Dasa is looking to be financed into production, it is hoped that global zinc markets will hopefully have recovered and the project-level debt at BST (US$22.85M) should be paid down to a sufficient level to enable meaningful dividend flow back up to head company level. It is not surprising, therefore, that Global Atomic appears to have put Dasa and the new PEA front and centre in its marketing materials, and that the marketing of BST appears to have been dialled down. Nevertheless, the BST operation (49% GLO) does give Global Atomic strategic optionality when it comes to financing Dasa. For the future financing the options include selling the stake in BST outright, using it as collateral for corporate debt, or as a basis for a convertible bond.

Capital Structure

Directors and management own approximately 13% of the issued shares, with Stephen G. Roman owning 10% of that total. The list of other major shareholders from the Q2 presentation includes: the Frame Group (7%), Sachem Cove (7%), Befesa (4%), Canaccord (4%), Deutsche Rohstoff (3%), with 66% free float. The Frame Group, Stephen Roman said in a recent interview is a friend of his, and Befesa are partners in BST in Turkey. Sachem Cove is the uranium fund headed by Mike Alkin.

Global Atomic was formed in 2005 and stayed private until 2017. In 2017, Global Atomic (with the uranium in Niger) merged with Silvermet Inc. (with the BST steel dust operation in Turkey) which had a TSX.V listing. Both companies were founded by Stephen Roman, and at the time of the transaction, Stephen G. Roman, Doug Scharf and Derek Rance were directors of both Silvermet and Global Atomic. Rein Lehari was a director of Silvermet and an officer of Global Atomic. Tim Campbell was an officer of both Silvermet and Global Atomic. As a group, these Non-Arms’ Length Parties held 8.5% of the common shares of Global Atomic and 11.6% of the common shares of Silvermet. Stephen Roman, Derek Rance, Rein Lehari and Tim Campbell are all still directors or officers of Global Atomic.

As can be seen from the share price graph (shown below) the combination has been a successful one. From 33c after the merger completed, the company has risen to a current level of 70c. Importantly, as the shares have increased in value, with Dasa advancing and BST being expanded, so liquidity has also increased, rising threefold in the past eighteen months. The increase in liquidity is almost certainly partly linked to the fact that in May 2019 Global Atomic was admitted to the Toronto main board, graduating from the Venture exchange. Furthermore, in September 2019 Global Atomic upgraded its OTC listing to the QX status.

Commodity

Global Atomic is unusual in that it is a uranium development company with the support of cash flow from a non-operated share in a recycling business that processes Electric Arc Furnace Dust (EAFD) to recover zinc concentrates. The recycling operation is not a depleting asset like a mineral deposit, but it is based on metals and so the fortunes of Global Atomic do, to some extent, depend on the capacity utilisation of the Turkish steel industry, and zinc prices. Fundamentally, however, the value of Global Atomic hinges on the uranium price.

Uranium

Uranium demand is predominantly driven by nuclear energy, and nuclear energy is a key element of global energy supply. Advocates of nuclear energy point to the fact that it has the lowest non-carbon operating cost per megawatt hour (MWh), and that the energy it produces has one of the lowest carbon emissions per MWh. Not only that but nuclear energy provides reliable base load power, it is sustainable and it is increasingly being recognised as a contributor to a low carbon future. Historically nuclear power plants have been expensive and slow to build and commission but the emergence of Small Modular Reactors (SMR)s is attracting more and more interest.

The World Nuclear Association (WNA) estimates a total of 175 million pounds of uranium is needed to power the current fleet of 441 operating reactors. Demand is forecast to grow weakly, with new reactors under construction, in planning or being proposed, off-set against accelerated closures in the existing fleet.

China has twelve reactors currently under construction, with 42 planned. India has seven in construction with 14 planned. Russia has four in construction with 24 planned; and the UAE has four under construction. Off-setting this picture of global growth in nuclear energy some governments are reducing reliance on nuclear. Belgium, Germany, Spain and Switzerland have proposed phasing out nuclear energy by 2030. France is reducing its reliance on nuclear energy from 74% of the energy mix and after Fukushima Japan would like to move away from nuclear energy, but since it needs to import about 90% of its energy requirements finding an alternative is proving difficult. It may be that nuclear energy may be the least bad option for Japan, and the country is now planning for nuclear to contribute at least 20% of total energy by 2030 from a depleted fleet and eighteen reactors are currently in the process of restart approval.

Globally there are 54 reactors currently under construction, 109 are ‘planned’ and a further 330 are ‘proposed’ according to the WNA. Demand growth can be categorised as weak, but growth nonetheless.

In contrast to the growing demand scenario, supply of uranium has collapsed due to a ten-year bear market. Uranium fell below $50/ lb in 2011 and has been in the doldrums since then, spending much of the last five years below $30/lb. Low prices have caused a number of closures and suspensions since 2017, gradually chipping away at primary supply. Recent announcements of the Cigar Lake temporary suspension and Kazatomprom production curtailments have caused the market to tighten, and spot prices have jumped from $24/lb to $34/lb.

Perhaps more importantly, the underinvestment in exploration and development is leading to a potential future supply gap. In times of falling prices producers cull non-core expenditure, starting with regional exploration and growth strategies. Ultimately producers end up high-grading deposits for survival and reducing investment on sustaining capital. When prices eventually change and start to rise there is usually a considerable lag before supply comes back on stream. Existing operations struggle to grow, restarting suspended operations is slow and complex, mineral resource inventories are depleted, and new mines are always several years away from completion.

With demand growing, and supply falling, the market is set to enter into a period of sustained supply / demand deficit. It is precisely this environment which causes sustained price rises. Industry consensus is that prices of between $50-60/lb are required to stimulate the investment in new supply that is visible among the list of new projects worldwide. Cameco and Kazatomprom have indicated that prices of $40-50/lb would trigger the return of operations in Canada (McArthur River or Cigar Lake) and Kazakhstan.

Much more likely is the scenario where demand in the form of buying from utilities strengthens at a time when the lack of supply response becomes apparent. At that moment demand requirements are largely price insensitive and the spot price can rise rapidly. An unsustainable price rise lasting several months to a year or two will ensue. It is what happens in almost every cycle in every commodity. Predicting the timing of the breakout is difficult, although given the price response in the past six weeks it is likely that the process has already begun. The uranium market is about to get very interesting.

Zinc

Zinc is an industrial metal, and zinc prices are intimately linked with industrial production levels globally. Classic commodity price analysis states that base metal prices vary with the rate of change of industrial production, rather than with absolute levels. So, if industrial production is growing, but growing faster than last year, prices would be expected to rise. Similarly, industrial production is growing, but growing slower than last year, prices would be expected to fall.

As it happens Global industrial production growth slowed in 2019 and zinc prices fell. So far, so consistent with theory. It is interesting to see that zinc prices throughout the coronavirus crisis have continued to show weakness, but they have not collapsed to the same extent that economic activity has collapsed. The reason for this is that zinc supply has been affected by Covid-19 closures and suspensions. Mines in Peru, Mexico and India have all been shuttered in attempts to manage the virus. Ultimately, however, it is expected that the demand destruction caused by the virus will weigh on the market in 2020 and 2021. Expect a year or two of low zinc prices.

Country

Niger

For an investment into Global Atomic, shareholders need to balance the good and the bad when it comes to country risk. Indeed, when it comes to critical decisions about Global Atomic, we rate Country Risk as being one of the most important factors for consideration. The good is that Niger is a country with uranium-rich geology and an unbroken fifty-year history of yellowcake production. The bad is that Niger is one of the poorest countries on Earth and it is surrounded by insurgency and conflict that is escalating. Ultimately you, the investor, need to analyse the two sides of the equation, and make a decision that suits your own individual risk profile. The Crux Investor argument is outlined below:

At its most basic, the Republic of Niger is a largely unpopulated state on the southern edge of the Sahara desert. It lies to the north of Nigeria, south of Algeria, east of Mali and Burkina Faso, west of Chad and it is a former French colony having achieved independence in 1960. The country is rated by the UN as one of the world’s least-developed nations and suffers from the Islamic insurgency in Mali and Burkina Faso, as well as the Boko Haram insurgency in the southeast, at the triple junction between Niger, Chad and Nigeria. The interior of Niger itself is relatively stable although the frontier regions have seen violent incursions in recent times. The US and the EU, has a significant military presence in the country, intended to combat Islamist militants. In Mali and Burkina Faso, and in northeastern Nigeria, the severity and the rate of the attacks is intensifying, leading to a deterioration of the situation on the borders of Niger.

When it comes to security of operations, Orano (ex-Areva), has experienced kidnappings (2007, 2010) and a suicide bombings (2013), but it has been incident free since then even as border incursions in the southwest of Niger have increased. Since 2015, Niger has struggled against a rising tide of jihadist attacks near the borders with Mali and Burkina Faso in the west, displacing nearly 78,000 people. And yet Orano has managed to keep producing uranium without disruption. In late 2019 and early 2020 significant raids were made into Niger by insurgents from Mali and Burkina Faso, killing almost 170 soldiers. Bases were overrun. Government forces hit back in February, killing around 120 insurgents.

The factors driving the conflict are complex and beyond the scope of this document, but seem to be a toxic mix of tribal mistrust, abject poverty, religious fundamentalism, gangster criminality, government ineptitude, and environmental degradation. Burkina Faso and eastern Mali have largely collapsed as functioning states and the OECD estimate that much of the insurgency is being fuelled by artisanal gold mining worth upwards of $2 billion a year. The concern is that the chaos will spill into southwestern Mali where the gold mines are operating, and east from the border into the rest of Niger, including the desert area in north-central Niger where the uranium is produced.

The questions for Niger becomes, what is Niger and the Rest of the World doing about the insurgency, and can normal business continue? Well, a number of stakeholders are taking active roles, and a short list of actors here includes: Niger, Orano, China, Turkey, the US, France and the EU.

Niger

Niger is now a key member of the G5 Sahel Joint Force, contributing over a thousand troops to the UN peacekeeping mission in Mali and receiving increasing amounts of military and technical assistance from foreign donors. Elections are due in 2021 and the country is also dealing with Covid-19. Given that Niger has lived through Ebola, a more fatal disease than this coronavirus, the country knows how to deal with these kinds of outbreaks so Covid-19 is the least of its troubles at present. Defending the borders appears to be the main task in hand.

President (since 2011) Issafou is a mining engineer by trade and was the National Director of mines in the 1980s (he understands mining). Issafou is not standing for re-election, and political analysts expect the power transition to be peaceful and in accordance with the constitution (Presidents can stand for two terms only). The “defence sector [however] scores very poorly in terms of operational risk, with its military doctrine lacking an appreciation of corruption as a strategic threat during deployments.” The army is stretched as it has to police the border with Nigeria, especially in the Diffa region, against incursions by Boko Haram. To the west the army has to contend with the jihadists from Burkina Faso and Niger. The ultimate security of the country now not only depends on Niger, but also on military support from France, the EU and the US.

As weak as the governance systems may be in-country, it is also important to remember that Niger as a whole understands how the uranium industry works. Aspects of a functioning industry such as water and radiation monitoring, logistics, supplies and above all the international bureaucracy and permitting surrounding radioactive material are all in place, and have been working since 1971 when production first began. Uranium production provides the country with a crucial source of revenue and political leverage. The World Bank estimates that Niger derived 13.3% of its income from natural resources (mostly uranium production) in 2017, and crucially that uranium provides up to 72% of its foreign exchange earnings.

Orano

Orano continues to produce uranium uninterrupted from its mines in Arlit. Little information is available, but for the company to have suffered three attacks from 2007 to 2013, but none since then indicates that individual companies can manage their own secure operations. The Cominak mine is due to close in 2021 because it has run out of ore. Orano will continue to produce from Somaïr for many more years, and it is studying the potential development of the large Imouraren deposit.

China

China helped build Niamey’s second bridge across the River Niger in 2010 and it is currently assisting with another bridge connecting the two sides of Niamey. Other China-Niger cooperation projects include the General Seyni Kountche Stadium in Niamey, Niamey’s Model Hospital, the Zinder Oil Refinery, and the Integrated Oil Project at Diffa. China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) built a uranium project at Azelik in 2010, although the operation was short-lived, closing finally in 2015. At this stage China has built an economic, not a defence-based, relationship with Niger. It also seems that China is not allowing the instability of Niger’s neighbours, nor the fragility of Niger’s armed forces to impede its investment in-country.

US

The US has a significant military presence, with more bases in Niger than in any other country on the continent, as part of Operation Juniper Shield, a wide-ranging counterterrorism effort in northwest Africa. Juniper Shield continues currently involves about 800 US troops operating from six outposts in Niger of which two are “enduring” US bases. One of them, Agadez, is the US’s key regional hub for air operations. After years of construction delays, US drones began flying both surveillance and armed missions from Agadez’s Air Base 201 in 2019.

Further construction projects at Air Base 201, Agadez are slated for 2021 and 2022, to increase the base’s fuel-storage capacity, fuel-distribution infrastructure, and strategic airlift parking areas, as well as provide better roadways on the expanding outpost. Media sources quote US intelligence documents stating that counterterrorism efforts are expected to last for the next 10 to 20 years; and that Niger is geographically positioned to enable support to multiple efforts integral to Africom’s missions.

EU

France is now flying drone missions from air bases near Niamey into Mali and Burkina Faso. The EU has a presence as part of the broader Sahel operations against insurgency. Although the EU strategy in Niger is partly military support, it is worth noting that the EU is also implementing policies in Africa to stem the flow of migrants to the Mediterranean, recognizing that the two continents’ futures are closely intertwined. In 2015, the European Commission launched an “Emergency Trust Fund for stability and addressing root causes of irregular migration and displaced persons in Africa”, spending on migration-related projects in Niger, including everything from migrant counseling to job training.

Turkey

Like China, Turkey is using soft power instruments such as humanitarian and development aid programs in its aim of increasing economic and strategic relations with African countries such as Niger. A Turkish group has built the new airport, and the new 189 room Radisson Blu in Niamey. Turkey views Niger as a key partner in its West African economic growth strategy, and aims to “establish a sustainable model... by developing concrete public and private cooperation projects.”

In conclusion, Niger appears to be strategically placed as a reliable partner in West Africa. It lies on the migrant routes north to the Mediterranean and as such is gaining from EU support to try and control that process. US and EU forces have surveillance and armed drone missions that are being used against the insurgency in Burkina Faso and Mali, which in turn is increasing in intensity and range. The number of attacks is estimated to be doubling every year. Despite the weak regional picture, China and Turkey have strategic investment plans for bilateral trade in the country. Not only that Orano continues to operate it’s mine’s without interruption and Niger continues to receive revenues and royalties from the mines. We believe that an asset as important as Dasa can and will be developed in a country like Niger. Furthermore Global Atomic is a Canadian company and Niger is assiduous in courting international support to help its Developmental goals and the uranium industry is vital for the economic well-being of the country. All in all it is likely that significant extra security is needed to operate Dasa safely but that it can be done.

Turkey

Turkey is nominally a secular democracy led by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Since the 2017 referendum the government has shifted to an executive presidential system of government and President Erdoğan now holds the majority of decision making powers within Turkey. While the political changes run counter to western democratic sensibilities, the government is aware of the importance of economic and infrastructure development in continuing to hold power. Turkey is the world’s 17th largest economy with $721bn GDP and it aims to be the one of the world’s 10 largest economies by 2023.

Turkey has the youngest and fastest growing population in Europe (700,000 graduates per year) and Istanbul’s economy alone is larger than the collective economies of twelve EU countries. It is worth noting that Turkey has the world’s second largest contracting sector, after China, and is expanding its bilateral trade into West Africa, including into Niger.

For BST, the business risks can be considered to be very low. The bulk of Turkey’s economy is made up of a diversified services sector including real estate, tourism, financial services, education, health, industry and agriculture. Industry continues to play an important role, and BST is essentially a good local corporate citizen that employs Turkish workers and no expatriates. For Global Atomic and Befesa, it is beneficial that the zinc concentrates are sold in dollars at the port immediately adjacent to the plant in Iskenderun as this minimises exposure to currency risk.

Uranium projects, Niger

Global Atomic has four projects in Niger, of which by far the most important is Dasa, on the Adrar Emoles 3 Licence area. Dasa was discovered by Global Atomic through grass roots exploration in 2010, and it is a classic example of creating lasting capital value through smart geological thinking, and good detective work with a drill rig. The other three discoveries made by Global Atomic prior to 2010 have minimal value in comparison to Dasa, and are not discussed in this report.

Apart from the fact that it is in Niger, Dasa is probably one of the best resources in the world. The resource is high grade, it has clean metallurgy, and the deposit is in the middle of the desert with plenty of space around it. There is enough water to run the plant and mine, but not so much water that it is a problem. The high grade material starts relatively close to the surface, and the deposit is large. Although the PEA focuses on the Phase 1, there are significant quantities of inferred resources that will enable Phases 2 and 3, and the deposit is open at depth and along strike. Importantly, the deposit has high grade portions that are open along strike and at depth, suggesting that large tonnes of material can be added with relatively constrained drilling campaigns.

In April, Global Atomic announced a new PEA for Dasa, comprising an optimized Phase 1 of a larger mine development at the Dasa Project that had been studied in the previous PEA dating from November 2018. The new Phase 1 plan is “a low Capex development targeting profitable production over a twelve year mine life.” The plan is to mine the first 48 million pounds of uranium, most of which is in the indicated category already, and while the Phase 1 mine is in progress, to upgrade the rest of mineral resources outside of the Phase 1 mine plan to feed a larger, future mine plan.

Highlights of the PEA are as follows:

- After-tax NPV8 of $211 million and after-tax IRR of 26.6%

- Cash cost of $16.72 per pound

- All-in sustaining cost (“AISC”) of $18.39 per pound

- Average annual steady-state uranium production of 4.4 million pounds U3O8

- Initial capital costs of $203 million, including 20% contingency

- Phase 1 Project mine life of 12 years, mining 48 million pounds U3O8 @ 5,396ppm

A differentiator between Dasa and other uranium projects is that this study was completed using a $35/lb uranium price. Simply by taking this lower price for the base case model indicated that Dasa can come into production even in a low uranium price environment. The project has a staggering capital efficiency, as can be demonstrated by the all-in-sustaining-cost (AISC) per pound of uranium coming in below $19/ lb, and less than $2/lb more than the cash operating costs. It is also impressive to note that the AISC definition used in the study includes “mining, processing and site general and administrative costs, royalty, offsite costs and sustaining capital expenditures, divided by payable uranium of 44.1 million pounds U3O8.”

The base case ($35/lb) internal rate of return (IRR) of 27% is impressive enough, as is the net present value of $211m, but the real value starts to pile up when consensus long-term uranium prices are used. With a long-term uranium price of $50 per pound, the project IRR increases to 46.3% and the NPV8 to $485 million.

The development plan is a low capex route into production that uses conventional underground mining and a processing technology similar to that used by the two existing uranium mines in Niger. This mine plan also provides future access to the contained uranium inventory of over 200 million pounds in the mine’s deeper horizons.

PEA Overview

The Study was based on Mineral Resources published in 2019, albeit the actual resource figures are presented as if for an open pit. As part of the July news release, a grade / tonnage report was included, showing quantities of Indicated and Inferred resources are present in the model at different cut-off grades. What this does not tell us, is how much of these resources are available in any underground mine plan. The recently published PEA does, however, show that the Phase 1 mining plan is predominantly based on the Flank Zone (and partly in additional stratabound lenses), and that it will be targeting 4 million tonnes of material over twelve years, at an average grade of 5,396 ppm (0.54%) U3O8. This is an extraordinarily high grade for any deposit outside of the Athabasca basin in Canada, and the cut-off grade of 2,300 ppm U3O8 is three or four times higher than most of the average grades of deposits slated for production around the world. Dasa is expected to produce over four million pounds of U3O8 annually.

Summary project metrics are shown in the table below:

Mining and Resources

The proposed development is for an underground mine using a sublevel blast-hole retreat with cemented paste backfill on a 20 meter sublevel spacing. This mining method ensures total ore extraction, but does require the company to fully develop to the bottom of every section of four levels before extraction can begin.

In the case of Dasa, with the mineralisation starting at approximately 70m below surface, the mine will have to be developed to a depth of approximately 150 metres before production can begin (4 levels of 20 m metres each is 80m, plus the original 70m, is 150m).

Processing

Global Atomic has stated that the Project will use conventional uranium processing techniques, similar used by Orano up at Arlit. Recoveries of 92% have been used, and the plant is designed with a capacity of 1,000 tonnes per day (t/d) or 365,000 tonnes per annum (t/a) using a modularised design. Layout has been optimised to enable the addition of more processing lines in the future, which is a sensible approach. If there is a Phase 2 period of lower grades, it might be appropriate to increase throughput to ensure annual production remains steady.

Value Opportunities

The new PEA also discussed some value opportunities. One of these is the possibility to truck ore, based on a Memorandum of Understanding (“MOU”) with Orano Mining, to supply a minimum 100,000 tonnes of uranium-bearing rock per annum to Orano’s operations in Arlit, approximately 100 kilometers north of the Dasa Project, for a minimum of 5 years, based on an agreement signed in July 2017. Discussions between the two companies regarding this development opportunity are on-going, and Global Atomic has mentioned this in every news release and presentation for years now. The Company believes that a successful conclusion would result in Global Atomic having reduced up-front capital requirements for commencing the project. As stated earlier in this report, Crux believes that the new development, with its manageable capital requirement is a much stronger proposition as a standalone project. The benefits of a reduced Capex are offset by a loss of control on the final yellowcake product and project delivery, a destruction of strategic value, and an increased operating cost.

More promisingly, the new PEA discusses the future exploration potential at Dasa. A large volume of mineralised material in the Inferred Resource category is present in the flat-lying portions of the graben between 400 meters and 800 meters below surface that could be mined in future decades. In addition the deposit remains open along strike and at depth.

Reiterating what was said at the beginning of this section, Dasa is one of the best undeveloped deposits in the world at present.

BST, Iskenderun, Turkey

As the website says, “Global Atomic holds a 49% stake in Befesa Silvermet Turkey, SL (BST), with Befesa S.A, a metallurgical company with operations in aluminium slag recycling and steel dust recycling, holding the remaining 51%. Befesa SA is the operator of BST and is listed on the Frankfurt exchange (FRA: BFSA).” BST purchases electric arc furnace dust (EAFD) mostly from local steel furnaces, roasts the dust in a Waelz kiln, to produce a zinc oxide concentrate that is then sold in US dollars at the nearby port of Iskenderun to customers that include Glencore and Nyrstar.

Silvermet Inc. was a Stephen G. Roman company, founded in 2005, at the same time as he set up Global Atomic Corporation. In 2008 Silvermet bought the Iskenderun plant, and a year later invited Befesa S.A (which was a private company at the time) to be its partner, renaming it Befesa Silvermet Turkey, or BST, in the process. As Silvermet held a minority, non-operated position in a recycling plant it failed to set the world alight as a TSXV company, but crucially it did survive the terrible resources downturn from 2012 onwards. In 2017 Global Atomic knew it had a tiger by the tail in Dasa but funding private African exploration uranium companies was nigh impossible, and so the business combination was proposed. Zinc was having it’s once-a-decade good year, meaning that once the merger was complete, the enlarged entity received a dividend from BST of C$7M, and with that windfall capital new high grade discoveries Dasa were made.

In 2019 a major expansion and refurbishment of BST took place, expanding throughput capacity from 60,000 tpa to 110,000 tpa. Anticipated zinc production would rise to 60 Mlbpa, up from 30 Mlbpa, assuming operation at full capacity. Global Atomic indicated that production would be at approximately 75% capacity in 2020, although with the evolving Covid-19 situation and its impact on the economy, it is hard to know if these levels will be reached.

The 2019 expansion was paid for out of operating cash flow, and debt. The project-level debt (100%) currently consists of US$6 million with Turkish banks, and US$16.85 million with Befesa, the operating partner. Half of this (US$11.5M) rests with Global Atomic. Having previously been expected to be paid off during 2020, the lower throughput and zinc prices now lead Global Atomic to expect payout of the US$8.42M Befesa debt over two years, 2020 and 2021. Given that Global Atomic receives dividend payouts from BST four months after the year end, this would indicate that the dividend payment for April 2021 and April 2022 will be zero. Depending on zinc prices and throughput rates, the earliest date for a meaningful dividend will be April 2023. Regarding the outstanding Turkish debts, the bank loans mature in 12 months but are expected to rollover and bear interest at rates of 3.3% to 3.8%. The Befesa loans mature between May and December 2021 and bear interest at rates of 5.9% to 6.6%.

The BST operation is more of an annuity than a mine development. The fact that it produces a zinc concentrate slightly disguises the fact that the stake in BST is a very useful financial tool. Recycling companies typically trade at ten times cash flow multiples, as opposed to mining companies (depleting assets) which trade at around 7-8 times cash flow. This would suggest that in 2022 or 2023, when the attributable cash flow from BST could reasonably be expected to have rebounded to the US$10 million level, the value of the 49% stake in the business held by Global Atomic could legitimately be in the region of US$100M. This value could be set against the capital requirement for Dasa at around the same time (2022 or 2023), to provide some kind of financing solution at a critical development point for the company. How the value proposition emerges is, at this stage unclear, but it could easily be an outright sale of BST, or a convertible note or other debt instrument using the zinc cash flow as collateral. In this sense, BST is a financial tool that will help to unlock real capital value at Dasa in the future.

Management is Key

When it comes to junior mining companies, management is absolutely key. Getting the hiring right at the right level of development of the company is so important and yet it is very hard to get absolutely right. As a project evolves from the early stages of exploration and scoping economic potential, through the study phases of resource definition, representative metallurgical testwork and the bone-crunching requirements of Preliminary Economic Assessment, and Pre- and full Feasibility Study, so another team of specialists is required, so a different management bandwidth and expertise is required. And it does not get any easier when the feasibility study is completed as the Company then needs to swing into construction, commissioning and finally operation. Each stage of the company needs additional layers of skills and expertise, and in many cases just more people to help with the workload.

Global Atomic Corporation ran from 2005 to 2018 with a small core team, comprising Stephen Roman, George Flach (VP Exploration), Rein Lehari (CFO), Tim Campbell (Co Secretary), Peter Wollenberg (Geology) and Fergus Kerr (Mining). This core team did an excellent job in nurturing the Company through the great resources downturn from 2012, and completing the merger with Silvermet, and, by finding Dasa, making probably the best uranium discovery outside of the Athabasca basin (in Canada). In late 2018, just after the last financing Merlin Marr-Johnson (EVP) was hired, and most recently in April 2020, Ron Halas (COO) joined from Kinross. Marr-Johnson can be credited with improving the communication flow from the company, and in Ron Halas Global Atomic has hired someone with real and recent West African construction experience. Halas is a key man in the Company’s push towards production.

It is also true that uranium mining is a difficult commodity because there are so few uranium mines (and especially no recent mines) that there are not many people with true expertise. The uranium industry has very few veterans with valid skill sets. Looking at the mugshots and biographies of the Global Atomic team, it is clear that although none of them are in the first flush of youth, their uranium expertise is real.

Global Atomic looks as if it is building the right team at the right time to take Dasa into production.

Timelines: Plans, Delivery, Reality

Track Record

Global Atomic continues to set ambitious timetables for itself. Looking back through presentations and news releases dating from the time of the merger with Silvermet it is clear that Global Atomic is keen to start production at Dasa as soon as possible, but unfortunately reality has struggled to match up with the rhetoric. The company has a bad habit of making technical announcements that then include an airy promise of impossibly quick delivery of the next key development milestone, or indeed, of production itself. For example, in January 2018 the announcement of a new drilling campaign starting at Dasa was accompanied by a quote that “upon completion of the drill program, the Company intends to complete a Feasibility Study, mine plan and Environmental Impact Statement to obtain the required permits for production in order to start delivery of ore to” Orano. Similarly, in October 2018, a PEA on the full Dasa project was announced and in the same announcement Global Atomic said that “the Company is targeting to deliver a Feasibility Study and Environmental Impact Study by Q2 2019” and “the Company expects site preparation and mine development to be completed in six months, allowing the Company to access uranium bearing rock by Q3 2020.” Well!

It is always good to aim high. The problem with aiming too high, however, is that the timelines for key development milestones in the natural resources sector are well-established and not meeting stated goals counts as a mistake. Everyone knows that it takes time to drill, incorporate assays into the model, complete metallurgical testwork, and work through option studies, preliminary economic assessments, feasibility studies, permitting, financing, staffing, construction, commission and into production. It is possible to telescope some of these timelines when the project is metallurgically simple, or when the commodity is ‘easy’ mainstream, such as oxide gold, or when the Company is already producing with a battle-hardened team working seamlessly across geology, metallurgy, mining, and finance function, in a country where all of the consultancy teams are located, such as Canada, Australia, South Africa or the US, and to a lesser extent nations such as Peru, Chile and Ghana. However, when it comes to a highly specialized situation such as high grade uranium development in West Africa, one must be realistic about delivery timelines, if credibility is to be maintained.

In April 2019 Global Atomic promised an updated resource in Q2 2019 on an open pit, and a Feasibility Study (focused on delivering ore to Orano) to be published in Q4 2019. In the end, the resource was published in July, which was a minor slip-up. More interesting was the fact that the Q4 2019 Feasibility Study focusing on an open pit development to provide ore for the Orano mills near Arlit, turned into a new PEA studying an optimised underground mine plan to feed a stand-alone plant at Dasa itself - and the whole study was published in April 2020. There are clues to the changing mindset, such as slide #9 from the November 2019 presentation indicating that Trade-Off studies were taking place during 2019, and the fact that the PFS study would focus on parameters such as being an underground mine minimising capex, and being economic at current uranium prices (it was US$24/lb at the time).

As it happens, the new PEA, published in April 2020 is a really great study. The quality of the work looks good, and it achieves the key parameters of having low capital costs, low operating costs, and great economics. It is also a low tonnage, high grade underground mine.

Next steps

The current Global Atomic presentation is more nuanced than previous iterations, stating that the company will deliver a mine permit application in H2 2020, and continue with production studies in 2021. The year end results (30 March 2020) provided a more detailed outlook statement, noting that Environmental Impact (“EIS”) and Hydrogeology Studies are underway, with field work being completed in compliance with Niger Government guidelines regarding the COVID-19 coronavirus. The news release went on to note that Global Atomic will combine the PEA, the Hydrogeology report and EIS into a Final Technical Report (“FTR”). The FTR is the key mining permit application document that will be submitted to the Government of Niger later this year.

More reasonable targets were outlined, including, limited infill drilling aiming to upgrade certain Inferred Resources to Indicated Resources in the current mine plan, and the anticipated issuance of the Mining Permit in 2021.

Finally, in more circumspect language Global Atomic notes that “Once the Mine Permit is issued, [the Company] will be in a position to finalize the engineering and geotechnical work needed to construct the project. It is good to see that Global Atomic has reined in its impulses to be overly optimistic in its timelines, and is adopting more conservative language.

Looking further ahead, it is reasonable to assume that 2020 will be devoted to delivering a mine permit for Dasa. Given that Dasa currently only has a PEA-level study carried out on it, and the uranium price is moving higher 2021 will probably be preoccupied by the completion of a Feasibility Study. Given that the Company has spoken about the need to carry out infill drilling and geotechnical drilling, it is possible that the Feasibility Study will take eighteen months to complete, which means that either Global Atomic starts the drilling programme in 2020 (itself a choice probably determined by Treasury levels), or that the Feasibility Study is published some time in 2022. Add in another two years (at least) for financing and construction, and first production could optimistically be put at 2024. Indeed, getting into production in 2025 would be no disgrace.

ESG

Environmental, Social and Governance are critically important ‘soft’ issues that demonstrate if a mining company is really working well or not. When ESG goes wrong, the soft issues suddenly become hard issues, and when ESG goes right there are so many other factors going right that it is easy to overlook the importance of ESG. Governance is a classic example of

Luckily for Global Atomic, the Dasa project is located in the middle of the Niger desert, in a highly uraniferous region. Population is scant, and the background radiation levels of the entire area is already elevated. The Environmental and Social context is ideal for mine development (security aside, although that was discussed in the Country section).

Interestingly, the Cominak mine owned by Orano is slated for closure in April 2021, which means that the government of Niger will lose one of its key sources of revenue, and that a large number of workers in Arlit will be unemployed. Global Atomic has mentioned in interview several times that the government is pressing the Company to accelerate its plans. It is encouraging to see a government vocally supporting mine development within a country.

On Governance, Crux has a long-standing preference for companies where key roles within are not held by a single person. The house view is that it is poor corporate governance to have one person be the Chairman and CEO in any company. Global Atomic is no different, and ideally Stephen Roman would choose to split the role and choose one or the other of the positions. Since he is one of the Company’s largest shareholders, and SEDI declarations indicate that he has built much of his position by buying shares in the open market, it is likely that he would choose to become Executive Chairman over anything else.

When will the Company need to raise money again?

Global Atomic, as at 31 December had C$3.8 million in treasury, so it probably has close to C$3M by now. Past accounts, adjusted for exceptional items, indicate that G&A is approximately C$2 million per annum. Looking at the timelines indicated by the Company and our own assessments, key operational milestones seem to be as follows:

- H1 2021, receipt of mine permit for Dasa

- 2022, Dasa feasibility study completion

- Q2 2023, restart of meaningful dividends from BST

Feasibility Studies typically cost a few million dollars to do well. In the case of Dasa, where Global Atomic is skipping Pre-Feasibility and going straight into Feasibility, complete with geotechnical drilling and infill drilling, an estimate of US$5 million (~C$7 million) is probably not unreasonable, plus the two years’ G&A (C$4M), takes the total cost to reach feasibility of approximately C$11 million. Given that the company already has C$3M, the amount it needs to raise is in the vicinity of C$8M. To maintain a treasury buffer, however, it would be sensible to raise a little bit more, perhaps C$2M more, taking the total new money required to C$10M, which would give the Company two years plus some breathing room. Who knows, perhaps the Feasibility Study might take a little bit longer to complete?

In short, we believe that the Company needs to raise about C$10 million to complete the Feasibility Study, and that it could probably be done with the issuance of 20 million or fewer shares (i.e. above 50 cents). The market, institutions in particular, like to see companies sufficiently well funded to complete their key short-to-medium-term objectives.

Looking ahead to the ultimate financing of the construction of Dasa in Niger, Global Atomic is blessed with options. When the time comes, the 49% stake in BST will prove its worth. As noted in the section on BST above, BST is a financial tool that will help to unlock real capital value at Dasa in the future. A financing transaction using BST to contribute perhaps as much as half of the required total will leave a much more manageable slug of capital to be raised from traditional debt and equity sources. This means reduced dilution, reduced financial stress for Global Atomic, and therefore enhanced shareholder value. Enhanced shareholder value is music to the ears of Crux Investor.

Marketing: How does the Company communicate with investors?

Looking through corporate presentations in the uranium sector it is striking that almost every company fills the front end of the presentation with a lengthy discussion on the uranium market. Demand is strong, wada wada, supply has been curtailed, dah de dah, uranium prices will rise, tum te tum. Only when the last drops of optimism have been wrung out of the uranium price fundamentals do corporates turn to their own projects. Do not get us wrong, we are bullish on the uranium price. We simply point out that readers of uranium company presentations are probably already converted to a rising uranium price hypothesis. Why, then, do corporates allocate so much presentation space to the underlying commodity analysis. Could it be that the most exciting aspect of the company is a generic, external factor common to every other uranium development company? Could it be that the company’s lead project only works at a uranium price that is still far above the current spot price? Chapeau, then, to Global Atomic which leaves the crystal-ball-gazing to others and instead focuses on the fundamentals of the Company, specific to Global Atomic. These include the value and financial leverage of the 49% in BST, and the no-nonsense facts about Dasa in Niger. The deposit speaks for itself, and the numbers that have been published in the most recent PEA are a compelling investment case in their own right. It is, perhaps, no coincidence that the only other company that leads with the project is NexGen, and the two stand-out deposits worldwide at present are Arrow and Dasa.

Stepping back a bit, the way Global Atomic communicates with investors has improved significantly in the last eighteen months. Early presentations from 2018 and before were light on detail and heavy on promises of near-term production. Since 2019 the value proposition has been laid out more clearly, and timelines have become more realistic even though the exact status of the Dasa project was unclear during the course of 2019. Language surrounding trade-off studies and feasibility studies in press releases and in interviews was prone to vagueness. For much of last year it was hard to ascertain what type of study was being completed and when, and what kind of project was it anyway? Is that a PEA, a PFS or a Feasibility Study being done? If it is a Feasibility Study, have the contracts for work been signed, and what are the key parameters (such as uranium price) that are being used in the model? Is the company going to truck ore to Orano, and if so, what are the terms? Will the mine be an open pit (as per the most recent resource update) or an underground mine? So many questions.

The most recent announcement, on the new PEA, was a welcome project update that cleansed the market of any uncertainties. For the first time Dasa had strong and reliable economic data, the mining method was clear, the uranium price used was fantastic in that it was current and realistic. The Company clearly stated that it was pursuing a stand-alone route to construction, via a small tonnage, high grade underground mine. All of this is music to the ears of a market commentator. Large projects proposed by development companies should always be viewed with scepticism because the failure rate is high.

We look forward to Global Atomic continuing its job communicating its value proposition, writing clear news releases and maintaining a useful website.

Valuation

NPV

At first glance the valuation of Global Atomic is relatively straight-forward as the recent PEA has just given some valuation metrics of the Dasa uranium project. The table below shows that Dasa is worth $211M at a uranium price of $35/lb, rising to $485M at $50/lb.

Next, add in the value of the 49% stake in BST. Assuming operating costs of 55-60c per pound, a recovery over the next three years of zinc prices towards $1/lb, and Turkish steel industry capacity utilisation to 85%, Crux arrives at a net present value of $48.6M for Global Atomic’s attributable stake in BST.

These two NPVs, plus cash of US$2.3M (C$3M), give Global Atomic a Net Asset Value (NAV) of $211M + $49M + $2M = $262M, or C$349M. Expressed in value per share, this equates to C$2.40 per share. Note, this is versus a market capitalisation of C$87M, on a share price of 60c, which puts the company on 0.25x NAV. If consensus pricing is plugged in (say, $50/lb uranium), the valuation stretches to $536M, or C$714M (C$4.91 per share), lowering the multiple to 0.12x NAV.

For a Company to be trading on 0.25x NAV is punitive, let alone 0.12x NAV, especially when one considers the assets in the portfolio. Unlocking the 75% (88%?) discount to NAV will happen gradually, and even reaching a 50% discount to NAV would see a doubling or more of the share price (assuming no dilution). Assuming an increase in the number of shares to 300 million in issue to finance production, and a fuller value of BST being allocated (see below), the numbers look different. The per share value is C$1.38 at $35/lb uranium, and C$2.60 per share at $50/lb uranium.

Cash flow

Another way of looking at the 49% stake in BST is as a cash flowing asset that can be used to protect equity dilution. Because BST is not a mine, and therefore not a depleting asset, it can run and run as an annuity. Similar companies, including Befesa (Global Atomic’s partner) typically trade on 10x cash flow multiples, as opposed to the ~7x cash flow multiples of miners. The premium is given to the annuity over the depleting asset.

In two years’ time, BST should be returning approximately $10M per annum in free cash flow back to Global Atomic. At a 10x multiple, this could potentially be worth $100M to Global Atomic, which could be used as collateral in a convertible bond or other financial instrument, or indeed Global Atomic may choose to sell the stake. The key point is that it gives Global Atomic options to finance $100M of the $203M initial capex for Dasa, thereby future-proofing the equity from excessive dilution, and effectively doubling the value of the shares.

Strategic Value

It is important to remember that the uranium industry is incredibly strategic as access to clean, abundant energy is a matter of huge geopolitical importance. The Russians and the Chinese saw the currency of nuclear power generation decades ago and have laid out a clear strategy to increase its share in the energy mix. The US is only now waking up to the importance of nuclear energy.

In October 2006, the Russian Federation accepted the Federal Task Program “Development of Russia’s Atomic Power Complex from 2007- 2010, and to 2015”. This spelled out the direction or nuclear power into the future, covering every aspect of power generation, the nuclear fuel cycle, waste handling and decommissioning, and innovative nuclear technologies. Today Russia is a world leader in the fuel cycle, and importantly it sees the exports of nuclear goods and services as a major policy and economic objective.

Similarly China has laid down a strategic action plan for nuclear power generation and its role in the nuclear supply chain as it adapts and improves western technology. China has become largely self-sufficient in reactor design and construction, as well as other aspects of the fuel cycle. The impetus for nuclear power in China is increasingly due to air pollution from coal-fired plants and the country plans to have a closed nuclear fuel cycle. In order to do this, it needs to have control of mine supply as well. Chinese companies have bought a number of uranium deposits in the past, but none have the scale or the grade that the Dasa project owned by Global Atomic offers.

What are the preferred features in a deposit? Well, ideally it needs to be high grade with clean metallurgy , relatively low capex, large and long-life, short permitting timelines, and finally it needs secure title and tenure. Let us look at these parameters in turn:

Grade and metallurgy

It is self-evident that high grades and clean metallurgy contribute to project profitability. Low grade projects are much harder to make economic through price cycles and reduce operational flexibility significantly.

On a standalone basis projects in the Athabasca basin in Canada take first prize, with stunningly high grades. Denison, at Phoenix has grades of 19% U3O8, and NexGen, at Arrow, has grades of 4% U3O8, and Fission Uranium Corp, at Triple R, has grades of 2% U3O8.

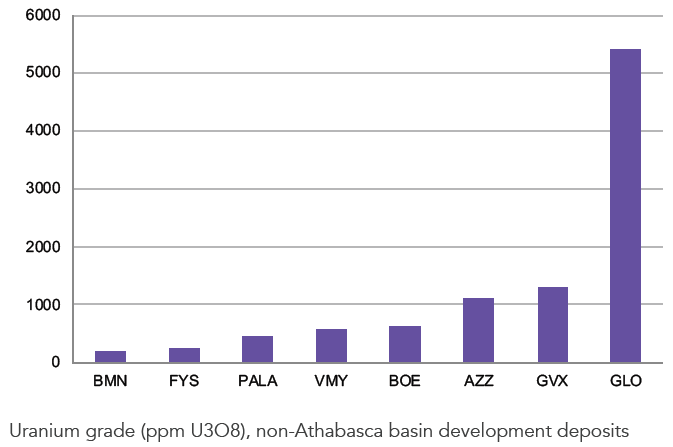

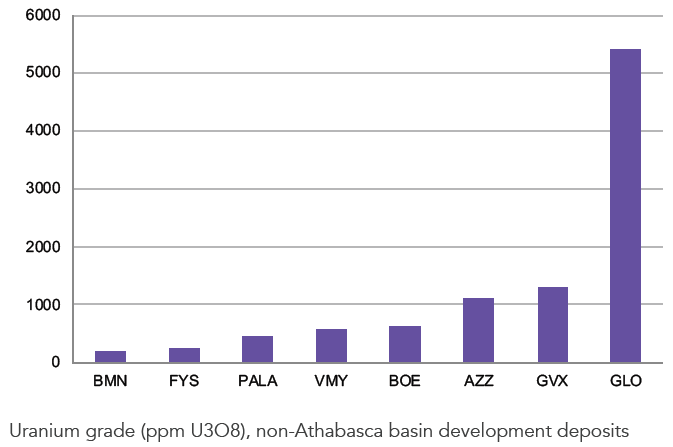

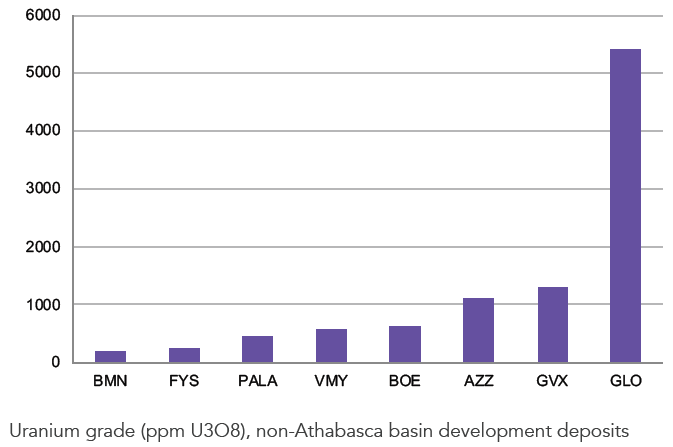

Outside of the Athabasca, grades of established deposits tail off dramatically. The grade at Dasa (5,396 ppm U3O8) is over eight times higher than the average of the deposits in the US, Namibia, Niger, and Australia.

Capex

The capital required to start production is another key factor when reviewing the ability of a junior company to go it alone, with credibility. The chart below shows the straight up capital that is required to start production. No surprises that the ISR projects and the restart projects are among the lowest capital. Dasa is the lowest capex project of the advanced new-build mines, and it is reflected in the AISC of $18/lb being less than $2/lb more than the cash operating cost of $17/lb in the PEA numbers.

Another way to look at it is the multiple of the current market capitalisation versus the capital it needs to raise to build the project. Ideally the capex required should not be many times larger than the market capitalisation if the company in question is to avoid what Crux Investor calls “The Market Cap Trap”. Clearly, if the capex required for a project is a large multiple of the market capitalisation then you have to ask questions about how the Company is going to finance the deposit without incurring massive shareholder dilution. In the case of Global Atomic, the capex for Dasa is $203M (according to the recent PEA), and if BST can be leveraged to the tune of $100M, then the shortfall to build Dasa is in the region of $100M. This figure, versus a market capitalisation of ~US$65M, shows that Global Atomic is not falling prey to the market cap trap. The Company should, therefore, be able to finance the mine without blowing out the capital structure. Accordingly, in our schematic assessment shown in Table 2, we have estimated the post-finance share count at Global Atomic to be 300 million shares in issue.

Permitting

A key determinant for uranium projects in this cycle is how quickly they can be permitted. Crux believes that Canada will take at least ten years to approve permits for new uranium deposits, and possibly as long as twenty years. New mines in Australia and in the US can take as long as in Canada, but where prior production has existed it can be quicker. It is only the African deposits of Namibia and Niger that can be permitted quickly, which is a function of how well established the uranium industry is in those countries, how sparsely populated and dry they are, and how much the economies rely on new generation mines. This observation is rarely talked about in the market and it has profound importance for the investment case for any of the Companies shown below. What it means is that the Canadian companies will probably only be developed in the next uranium cycle, not this one, thereby removing them as potential takeover targets for larger companies. This automatically elevates Nigerien and Namibian projects up the attractiveness index for investors.

Title and Tenure

The final aspect for consideration is title and tenure, and one might add security as well. Canada, Australia, and the US have excellent track records on Title and Tenure, but so do Niger and Namibia. Of all the countries, Niger needs international cooperation more than anyone else, and it also relies on the uranium industry more than anyone else. As discussed in the Country section above, it is an island of stability within a sea of instability. Crux believes that with appropriate attention to security, Dasa can proceed.

So what does this all mean?

Knowing that Global Atomic is trading at 0.24x NAV with a low uranium price is one thing. When the high grade, the low capex, the short permitting timelines, and the secure title are pulled together, Dasa is a stand-out deposit. With BST thrown in the mix to protect against equity dilution when it comes to building the mine, it is safe to say that Global Atomic is in a category of one. It is a unique company.

Red Flags

Working through this report, a number of red flags appear when researching Global Atomic. A collated list of concerns reads as follows:

- Instability in the Sahel, and security concerns in Niger.

- BST in Turkey is struggling with low zinc prices, high smelter charges, and a weak steel industry (dust availability).

- BST is now carrying $22.85M debt, so no BST dividend for Global Atomic until 2023.

- Rolling over the $6M debt with Turkish banks will be a key milestone later in 2020.

- Low zinc prices are expected to persist for a couple of years.

- Low cash balance. We estimate that the Company needs to raise about C$10M to complete the Feasibility Study.

- Combined CEO and Chairman roles is sub-optimal corporate governance.

- Global Atomic has struggled to meet its publicly stated delivery timelines.

- Language in interviews, news releases and presentations is not always consistent, and is often imprecise. More care to be taken with messaging please!

What we want to see

Regional insecurity in the Sahel and low zinc prices are macro phenomena, beyond the direct control of Global Atomic. Where management can improve is to tighten up the language it uses in the market-place, written or spoken. The assets are great, and better expectation management around them would grow credibility and attract more investors. Set the right tone, and then meet delivery promises. Please.

Key de-risking milestones are roll-over of the Turkish debt (Q3?), mining permit (Q4-early 2021?) and then financing, timings, appointments and delivery of the Feasibility Study.

Green Lights

- New PEA at Dasa highlights a phenomenal project.

- High grade, low cost, and strong economics on the Phase 1 mine.

- Simple metallurgy allows conventional processing, reducing technical risk.

- Small tonnage, conventional underground mining reduces technical risk.

- Phase 1 project easily scalable and provides gateway for development of remainder of the deposit.

- Dasa deposit open at depth and along strike. Significant existing resource of >250Mlbs with tremendous expansion potential at high grade.

- The only project to use $35/lb uranium as a base case (NPV8 = $211M. Value soars when consensus long-term prices are used.

- Global Atomic in a Category of 1 when it comes to all-round project strength, including permitting timelines.

- Strategic importance of Dasa when compared with peers globally. It is the only high grade, long-life, low capex asset that can be brought into production quickly thanks to permitting timelines. And it has tremendous exploration potential at its fringes.

- 49% stake in BST could potentially be worth $100m (10x cash flow) in 2022

- Low capex can be funded to a large extent by contribution from BST, offering superb protection from equity dilution

- Uranium price fundamentals strong as the market slips into sustained supply / demand deficit

Conclusion: What does this all mean?

Global Atomic Corporation is a uranium development company with a difference, a company that stands alone, in a Category of One. The two key differentiators in Global Atomic are the Dasa deposit itself, and the fact that its stake in BST is a financing chip that can be cashed when it comes to building Dasa.

The Dasa uranium deposit is a phenomenal discovery and is perhaps the most important mineral resource globally that will start production in the current uranium cycle. Dasa is large, with over 250 million pounds of mineralised material that has high grade intercepts open at depth and along strike meaning that the deposit has the potential to be even bigger than currently defined. It is the kind of resource that can sustain decades of production and it therefore has strategic value as a long-term source of supply for the long-term, strategic nuclear power generation industry. Dasa also has a high-grade front end that Global Atomic has designated as the target of a Phase 1 mine plan. This plan, laid out in a recent PEA, is to mine 0.5% grading material over twelve years to produce over four million pounds of yellowcake a year at $18/ lb AISC and a capex of $203M.

Economically and technically Dasa is better than any other project globally, apart from potentially one or two of the Canadian deposits in the Athabasca, but crucially it can be permitted within months whereas the Canadian deposits will take decades to permit. Global Atomic aims to have the mine permit in hand within a year before entering feasibility and the path to construction.

The 49% stake in the recycling business in Turkey, BST, will take two years to pay off its debts before emerging as a regular source of meaningful cash flow, potentially worth $100M to the Company. Global Atomic will be able to use the value of BST to reduce equity dilution when it comes to financing Dasa.

Challenges for Global Atomic are managing security risk in Niger, filling out the leadership into a properly staffed, build-ready team, tightening up the language it uses in the market, and topping up the treasury to ensure that the Company is well funded for the next two years.

Share valuations start from C$1.38 per share if the contract uranium price is $35/lb in two years’ time and the company share count stands at 300 million, rising to C$2.60 if the uranium price reaches $50/lb. Currently, the Net Asset Value of the company indicates a value of C$2.40 per share, which is four times higher than the share price today.

Your decision to invest (or not) should primarily hinge on your view on the uranium price and your assessment whether Global Atomic can replicate the security measures that Orano has in place to ensure uninterrupted supply of uranium from Niger. Crux believes that Global Atomic offers compelling value in a rising uranium market.

Appendix - Brief Summary

A very brief summary of Global Atomic is presented in the simple Question / Answer Format table below:

These CRUX Reports are written for expert investors AND for people new to natural resource investing. But whether you are an expert or a newbie, we all have the same driver. We invest to make money. Sometimes investors get emotional about the investment. They actually think they own a mine. They don’t. They own shares in a company. So focus on your investment strategy, work out the best plan for your needs, stick to the fundamentals and remember that the only way you make money is if your shares go up in value…assuming you don’t forget to cash them in!

Executive Summary

Global Atomic Corporation is a uranium development company with a difference, a company that stands alone, in a Category of One. The two key differentiators in Global Atomic are the Dasa deposit itself, and the fact that its stake in BST is a financing chip that can be cashed when it comes to building Dasa.

The Dasa uranium deposit is a phenomenal discovery and is perhaps the most important mineral resource globally that will start production in the current uranium cycle. Dasa is large, with over 250 million pounds of mineralised material that has high grade intercepts open at depth and along strike meaning that the deposit has the potential to be even bigger than currently defined. It is the kind of resource that can sustain decades of production and it therefore has strategic value as a long-term source of supply for the long-term, strategic nuclear power generation industry. Dasa also has a high-grade front end that Global Atomic has designated as the target of a Phase 1 mine plan. This plan, laid out in a recent PEA, is to mine 0.5% grading material over twelve years to produce over four million pounds of yellowcake a year at $18/lb AISC and a capex of $203M.

Economically and technically Dasa is better than any other project globally, apart from potentially one or two of the Canadian deposits in the Athabasca, but crucially it can be permitted within months whereas the Canadian deposits will take decades to permit. Global Atomic aims to have the mine permit in hand within a year before entering feasibility and the path to construction.

The 49% stake in the recycling business in Turkey, BST, will take two years to pay off its debts before emerging as a regular source of meaningful cash flow, potentially worth $100M to the Company. Global Atomic will be able to use the value of BST to reduce equity dilution when it comes to financing Dasa.

Challenges for Global Atomic are managing security risk in Niger, filling out the leadership into a properly staffed, build-ready team, tightening up the language it uses in the market, and topping up the treasury to ensure that the Company is well funded for the next two years.

Share valuations start from C$1.38 per share if the contract uranium price is $35/lb in two years’ time and the company share count stands at 300 million, rising to C$2.60 if the uranium price reaches $50/lb. Currently, the Net Asset Value of the company indicates a value of C$2.40 per share, which is four times higher than the share price today.

Your decision to invest (or not) should primarily hinge on your view on the uranium price and your assessment whether Global Atomic can replicate the security measures that Orano has in place to ensure uninterrupted supply of uranium from Niger. Crux believes that Global Atomic offers compelling value in a rising uranium market.

Introduction

Global Atomic is a development company with uranium assets in Niger, and operating cash flow from a zinc business that makes money from recycling steel dust in Turkey. The company is headed by Stephen G. Roman, an industry veteran with a uranium background who has built up an exploration and development team around him. Global Atomic was formed in 2005 as a private company, and in 2017 it merged with Silvermet, another Roman vehicle, that owned the recycling plant in Turkey and was listed on the TSX Venture exchange.

The Company aims to start uranium production at the 100% owned Dasa project, and it has just published a new PEA based on an optimized twelve year mine plan. Global Atomic is now in the process of applying for a Mining Permit prior to moving into the Feasibility stage. The Company anticipates receiving the Mining Permit in Q1 of 2021, and aims to have completed the Feasibility Study in early 2022.

In addition to the uranium project, Global Atomic has a 49% stake in the BST steel dust recycling operation in Turkey that produces zinc concentrate and provides financial leverage to minimise equity dilution. The plant was expanded in 2019 increasing throughput capacity to 110,000 tonnes annually up from 60,000 tonnes a year. At full capacity the expanded BST could produce 60 million pounds of zinc concentrate a year, although the Company has issued guidance that 2020 output is expected to be approximately 45 million pounds, suggesting capacity utilisation of approximately 75%. BST is carrying US$22.85 million of debt at the project level, which it expects to pay off in two years.

Strategy. What is the Company planning to do?

Global Atomic plans to bring the Dasa uranium project, in the Republic of Niger into production and in interviews Stephen Roman has stated that the team are miners, and that Global Atomic is a mining company. The website and presentation also promote the fact that the Company has a non-dilutive strategy as the company is supported by cash flow from the recycling facility in Turkey; and a potentially low-cost route into production through the trucking of ore to Orano under the terms of an MOU signed in 2017.

The strategy of the Company does seem to have changed over recent years. In late 2018 the Company published a Preliminary Economic Assessment (“PEA”) on Dasa, using a US$50/lb uranium price with a capex of US$320 million, with a view to producing 7.5 million pounds per annum on production. These results put the project in the same category of almost every other uranium project, which is to say a high capex project profitable when uranium prices reach US$50/lb. Given the fact that uranium prices were firmly entrenched in the US$23-25/ lb range, plus final the results of the drilling from 2018 were only published in early 2019, Global Atomic soon announced that it would reanalyse the project, with a view to it being profitable at low prices. The fruits of that work has been revealed in the new PEA, published in April 2020.

Also included in the 2018 PEA was a section devoted to the Alternative Mining Strategy which involved trucking ore to the Orano operations at Arlit some 120 kilometers to the north in Niger. This was seen as being a key way of getting started in a low uranium price environment, with reduced capex. The Company regularly refers to its ability to get into production quickly by trucking ore to Orano, and Stephen Roman often mentions this option in interviews.